La muerte nos fascina, nos encanta, nos seduce.

Death fascinates us, we love her, she seduces us.

Those were the first words I read when I started investigating my next blog topic the Day of the Dead in Mexico. I was shocked and confused at the same time. How can somebody love dead? I asked myself. And how can a whole nation love dead?

I continued reading and more sources confirmed that el Día de los Muertos is about celebrating and not mourning. I turned to my Mexican friends for explanation. Their smiles and confirmative reactions made me curious. So it´s true… I´d like to share with you what I´ve learned:

Day of the Dead History in a Nutshell

The Mesoamerican civilizations believed that the deceased played an important part in vital aspects of life such as harvest, reproduction, family, the fight against diseases, and life in the community in general. Death rituals and sacrifices were therefore a widespread practice among the ancient people of Mesoamerica.

The contemporary celebrations of el Día de los Muertos originate from Aztec mythology. The Aztecs dedicated an entire month to honoring and celebrating death. This was the month of Miccailhuitontli, which roughly corresponds to July 24 through August 12.

The month of the dead was led by goddess Mictecacihuatl, Lady of the Dead or goddess of the Underworld who ruled over the afterlife. There were many rituals to honor lost children and deceased adults; the Aztecs believed that the dead responded to the food offerings, flowers and prayers with fertility and vitality.

Like all traditions, the way the dead are celebrated in Mexico has changed over time. When the Spanish arrived they stopped the month long celebration and moved it to the first days of November.

Skull and Skeleton Symbolism

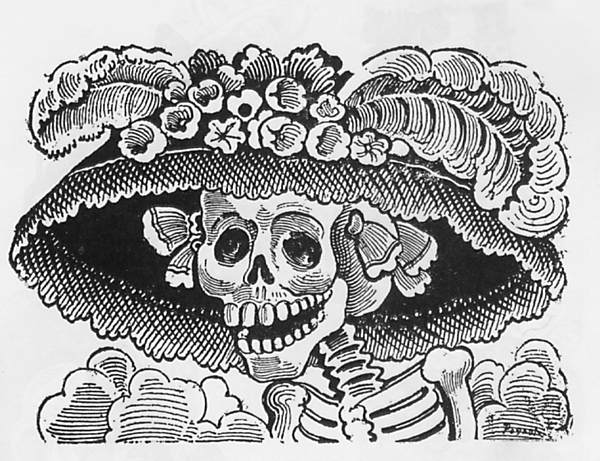

The skeleton and skull symbolism of the Day of the Dead goes back to the reigning period of the 29th president of Mexico Porfirio Díaz (1884 – 1911). The media on its part took up lead in printing skull caricatures as a means of criticism towards Diáz´ administration.

Mexican printmaker José Guadalupe Posada drew a whole bunch of skeleton prints criticizing the modernity as a machine of progress and destruction. The skeletons symbolized the wealthy and classy as cold and dead reflecting the miserable situation in the country in a satiric and ridiculing manner.

After the Mexican Revolution (1910), death became a popular source of inspiration for a wide range of Mexican artists. With humor and affection death was extensively studied or reflected in literature, poetry, cinema and art. The national obsession with death got stronger and gradually became inseparable from the Mexican identity.

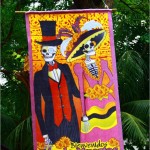

La Calavera Catrina – The Elegant Skull

Nowadays one of Posada´s figures is the most popular symbol of the Day of the Dead celebrations: La Calavera Catrina – The Elegant Skull. The original Catrina skull only wore a hat. Diego Rivera was the first to put clothes on her in his remarkable work Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park.

Ever since, creating skulls and skeletons became the nation’s biggest hobby: schools, institutions, cultural centers, tourist organizations and museums started organizing contests for the most beautiful offerings, shrines and catrinas. As a result, La Catrina became public art.

Nowadays you encounter Catrina in both genders and in countless designs, materials, and colors. She is always dressed up and has been reinterpreted as the general metaphor for death: The skeleton image is the symbol of universal death and the fundamental equality of life.

The Mexicans adore the personification of death and have even given her nicknames such as La Flaca (skinny), La Pelona (baldy) or La Huesa (bony). The amazing skull and skeleton artworks have resulted in modern art that also gained prestige and appreciation at international level.

The Mexican Philosophy of Life

So why is it that Mexicans like to play with skulls and skeletons? The answer seems to lie in the nature of the Mexican. Mexicans are happy people who always try to see the positive side of life. This goes hand in hand with 1) making fun of anyone and anything and 2) finding an excuse to celebrate at all times; it´s their philosophy of life.

One example of making fun of others is el albur mexicano. This is a bit off topic but it most certainly reflects the Mexican habit of ridiculing people. El albur is a phrase with double entendre of which one of the possible meanings is sexually related. The vulgarity is widespread across all social sectors.

Well, this type of (black) humor is also reflected in el Día de los Muertos. We are all going to die someday, so why not laugh at death and make fun of her?, so the Mexicans believe. Outsiders often perceive this attitude as disrespectful and misplaced towards the deceased.

“There is perhaps as much fear in his attitude as in that of others, but at least death is not hidden away.” Octavio Paz defends his people in The Labyrinth of Solitude. Paz´ comparison of the Mexican approach with the conservative attitude of westerners is very well-known:

Para el habitante de Nueva York, Paris o Londres, la muerte es la palabra que jamás se pronuncia porque quema los labios. El mexicano, en cambio, la frecuenta, la burla, la acaricia, duerme con ella, la festeja; es uno de sus juguetes favoritos y su amor más permanente.

The word ‘death’ is not pronounced in New York, in Paris, in London, because it burns the lips…The Mexican, in contrast, is familiar with death, jokes about it, caresses it, sleeps with it, celebrates it; it is one of his favorite toys and his most steadfast love.

Modern Day Practices of the Day of the Dead

In the middle of the fun you will also see offerings and self-made altars; it is the serious part of remembering the honorable dead. Many believe that on November 1 the souls of the children return and on November 2 the adult dead come back to celebrate together. Therefore families decorate shrines with flowers, candles, and food offerings such as pan de muertos – Day of the Dead bread.

There is an abundance of self-made altars. You can find them at people´s houses, in the streets, and in malls and restaurants. The altars are thoroughly decorated with cempazuchitl flowers, colorful ribbons, candy skulls, Posada-like skulls of papel picado cut paper and favorite objects, food and drinks of the dead to make them feel at home.

The altars include multiple levels; the most common are two levels (symbolizing heaven and earth), three levels (symbolizing heaven, purgatory, and earth) or seven levels (symbolizing the seven steps necessary to reach heaven). On the ground in front of the altar a cross of salt is laid out for purification. A floral arch symbolizes the entrance to the world of the dead made out of the flower of the dead cempazuchitl.

El Día de los Muertos also seems to be a good excuse to spend some time together. There is live music in the cemeteries, people tread on the graves and raise their glasses. The Mexicans pray, sing, laugh and maybe cry.

Poetry to Ridicule Death

Another typical expression of the dead celebrations is the so-called literary calavera – a satirical verse intended to humorously criticize the living with death as central theme. Within the context of el Día de los Muertos, one of my dear Mexican friends wrote me a personal calavera. I tried to translate it into English but it completely loses its touch and it simply sounds bad, so for those who understand a bit of Spanish, there you go:

Marleen la Holandesa disfrutaba su cerveza

Concentrada en el bailongo y muy feliz en Tepetongo…

Inocente no sabía; que la huesuda sigilosa

Fijamente la veía, para llevársela

A su choza.

My interpretation of this beautiful poem is as follows: I am portrayed as the ignorant foreigner enjoying her life in Mexico not realizing that death will also come to catch me one day.

His message can be perceived as a reminder; we are all equal in the end. So why not ridicule death like the Mexicans do?

PHOTOS: Day of the Dead in Mexico

I think it´s symbolism and colors give this day a mysterious touch. Click through the pictures for an impression of el Día de los Muertos in Guadalajara, Tlaquepaque and Zihuatanejo.